If you’re in the mood to read a literary novel, consider the classic: The House of Mirth. If you’re attracted to The Gilded Age on HBO, it will seem familiar. Be forewarned that my book review here contains spoilers. This is a challenging novel to read, but worth the effort.

Before you get misled by the title of Edith Wharton’s masterpiece, know that “mirth” is ironic. The House of Mirth (1905) depicts members of New York elite society during the Gilded Age, of which Wharton was a part.

Our heroine, Lily Bart, wants to be a part of high society, but with little money, her beauty is her ticket to permanent residence — she must marry a rich man. She falls in love with Lawrence Selden, but he doesn’t have the wealth to keep her in the style to which she has become accustomed. Lily has many rich suitors from whom to choose, but they are boring, dim-witted, repugnant, or married. Lilly’s wit enables her to wrap anyone around her finger, yet she foolishly breaks society’s rules of impropriety to her detriment.

Like Elizabeth in Jane Austen’s Persuasion, Lily, at age twenty-nine, is at risk of passing her prime. Here’s an excerpt from Persuasion:

She [Elizabeth Elliot] had the remembrance of all this; she had the consciousness of being nine-and-twenty, to give her some regrets and some apprehensions. She was fully satisfied of being still quite as handsome as ever; but she felt her approach to the years of danger, and would have rejoiced to be certain of being properly solicited by baronet-blood within the next twelvemonth or two.

The House of Mirth, published eighty-eight years after Persuasion (1817) illustrates how little has changed for women.

After learning that the money Gus Trenor gave Lily was a bribe for sex rather than the proceeds of her invested money, she spends the novel attempting to pay him back to maintain her integrity and honor. (To my way of thinking, since he deceived her, she doesn’t owe him the money.)

Ironically, Lily spoils her chances to marry wealthy men (self-defeating personality disorder?) and ensure her place in high society but ends up living far lower when her money runs out and her pride prevents her from accepting help from others who want to help her.

I love the ending in which everything about Lily resolves to a zero balance in her checkbook. She’s made amends with her longtime love, Selden, she destroys the letters that could have scandalized him and her rival, Bertha Dorset, and she pays her “debt” to Gus Trenor and other shopkeepers. The tragedy, of course, is that she dies at the young age of twenty-nine.

Like the title, the story drips with ironic tragedy. Lily seeks to be accepted into a group of people in high society who use her for her beauty, betray her ruthlessly, and then wrongly shun her. Lily has more integrity and honor than they do, yet she suffers the most. This novel makes fun of people in a particular place and time, and yet its depiction of human wickedness and frailty is timeless.

I’m in a sophisticated and fun book group with writer Natalie Serber. Check out her substack here.

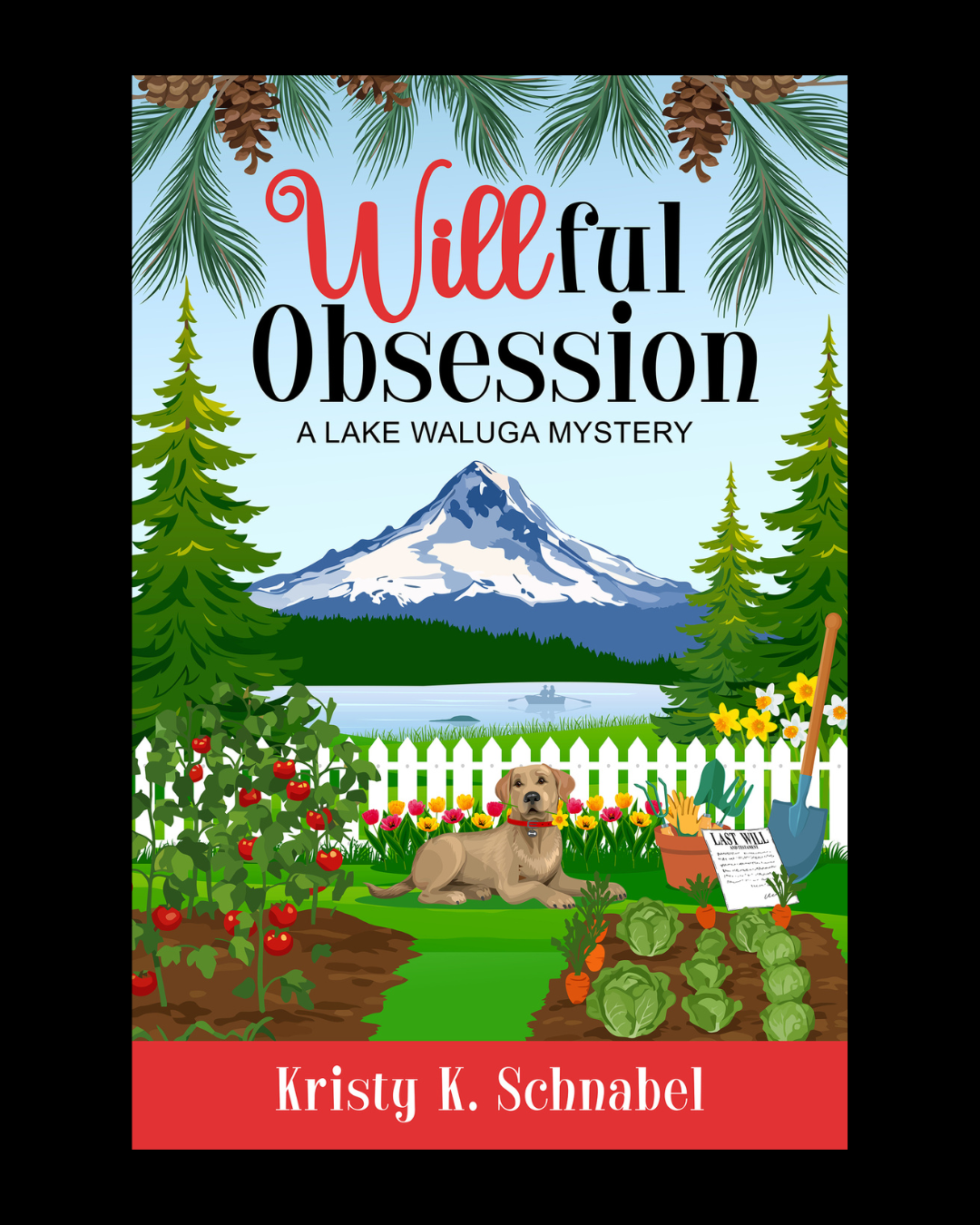

If you want to escape to a compelling, cozy mystery, check out Willful Obsession: A Lake Waluga Mystery. If you admire strong women amateur sleuths, suspenseful stories with surprising twists, quirky characters, a charming town with loads of secrets, community gardens and friendly neighborhoods, and most of all love animals, this story is for you. For reviews and to learn more head here.

Leave a comment